Paper presented at a symposium of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (139th Meeting, Philadelphia, December 1971): Value and Knowledge Requirements for Peace.

Introduction

In this paper the problem of peace is considered to be an ecological problem. Ecology is the study of the complex interrelationships between organisms and their environments. To clarify this approach, three major types of social complexity -- organizational, problem and conceptual -- are briefly reviewed together with their interactions and their effect on the individual. A practical approach to handling, generating, and facilitating comprehension of this complexity by the use of interactive computer graphics is then described in terms of its significance for a variety of users.

It is not the intention of this paper to suggest a new theoretical model to examine the problems of peace but rather to show the relevance of an existing device to many such enquiries. In demonstrating this relevance, it was useful to treat peace as an ecological problem because of the high tolerance of the ecological approach to complexity of the order detected in the psycho-social system. The closing sections comment on the relevance of this approach to value and knowledge requirements for peace and suggest some practical stepswhich could be taken.

Organizational complexity

The number of organizations active in any given field or geographical area is increasing.[3] The growth in the number of independent organizations has been paralleled by a fragmentation within the larger ones -- leading to a proliferation of sub-commissions and sub-sections. Accompanying these trends is an uncharted growth in the variety of forms of organized activity. These trends of divergence have been partially compensated by an increase in the inter-connectedness of organizations and efforts at establishing bodies with coordinating or integrating functions -- but these trends of convergence also contribute significantly to the complexity. Furthermore, this static organizational structure provides a framework for forms of dynamic, temporary or ad hoc organizations which are difficult to track systematically but are nevertheless a key feature of organizational life - particularly when organizations can be deliverately based on lags (or temporal "niches") in inter-organizational processes.

Knowledge complexity

The number of fields of knowledge is increasing. This growth has been paralleled by specialization or fragmentation within disciplines as they encompass a larger range of concepts. This leads to a proliferation of sub-specialities and sub-disciplines. Accompanying these trends is an uncharted growth in the variety of forms of organized conceptual activity and a multiplication of meanings associated with any given term. These trends have been partially compensated by increasing recognition of the interconnected or multidisciplinary nature of many areas of interest and there have been efforts at establishing integrative overviews of programs in each discipline and a general systems discipline. These relatively static features of the body of knowledge are accompanied by the formulation of unsubstantiated concepts as a basis for immediate action because dynamic features of the system ("lags") prevent the rapid location and integration of relevant tested knowledge existing elsewhere -- this increases complexity particularly when the existence of such temporal niches is deliberately exploited to generate false concepts. Much damage can be done before compensating processes can be brought to bear -- it is the "appearance of truth" rather than "truth" which is significant within the lag time.

Problem complexity

The number of recognized problems has risen rapidly, particularly with the advent of the environment issue. The growth in the number of problems has been paralleled by a recognition that each major problem needs to be broken down or fragmented into sub-problems. Accompanying these trends is an uncharted growth in the variety of problems. These trends of divergence have been partially compensated by a recognition of interlinkages between problems and efforts at locating the key or fundamental problem underlying a whole group. In the final stages, problems become "aggressively interactive" in that they do not remain docile and static but appear to have a momentum and initiative of their own. They increase or decrease in importance and manner of interaction without it being possible to determine the original cause of the change. The environment becomes turbulent and new short-term problems are generated in the vortices,

Comparison of approaches to complexity

There are other features common to the three types of complexity noted above:

1. Interest in the entity -- organization, concept, or problem -- is not such as to generate a methodology which would encourage systematic data collection. Samples are collected in terms of predefined categories but there is no effort to determine how many of each entity there are. Basically confusion still reigns as to the nature of an organization, a concept and a problem.

2. The consequence of (1) is that there are no statistics on the entities in each case. It is not known how many organizations are currently in existence, although different agencies may have some such information to facilitate program activity in their own spheres. Similarly the number of concepts current in different sectors of society is unknown, as is the number of problems. The lack of statistics follows naturally from a lack of any systematic lists of each type of entity -- for example, there is no list of "world problems".

3. The consequence of (1) and (2) is that there is little understanding of the variety of entities within each type of complexity. Each sector of society perceives a limited range of relevant entities and rejects others as of little interest or significance.

4. As a result of (3), the typologies developed reflect the special interests of the sector of society within which they are generated and tend to be very crude, ignoring grey areas and hybrid entities.

5. In each case concern is primarily with the "relevant" entity conceived in isolation from its context. The interest in inter- organizational relationships has only recently started building up, relationships between concepts is confined to those within each particular discipline -- inter-disciplinary and general systems approaches are suspect. Recognition of significant relationships between problems is governed by agency or departmental short-term program priorities. It is therefore not possible to determine systematically whether a particular type of entity or relationship is not present in a given setting.

6. The absence of typologies and a picture of interrelationships means that it is not possible to build a picture of the ecological system in each case. It is not possible to look at the ecological system constituted by a particular community of organizations of different types.? Nor is it possible to look at the ecology of a particular conceptual milieu.8 Again, the ecology of problems is fragmented into convenient administrative chunks by unintegrated mission-oriented agencies.

7. In each case the deliberate structuring of the approach to the different types of complexity results in various forms of "exclusive relevance" or "apartheid". One can speak of: an organizational apartheid which ignores the developmental requirements of particular types of organizations [9] a conceptual apartheid which ignores the significance of particular types of concept, and of a problem apartheid which ignores the significance of particular types of problems -- for each organization the only significant problems are the ones with which it is concerned.[10] There is no framework within which to consider all problems.

8. The exclusiveness noted in (7) occures at a time when the hierarchical structures reinforcing it are recognized to be crumbling or at least suspect. Stable institutions, conceptual systems and problem environments are threatened with dissolution.2 Nonhierarchical organizational structures are sought. Hierarchical classification of knowledge and rigid systems of categories are challenged, and simplistic groupings of problems are rejected. [4]

9. Despite the trend noted in (8), there is still, in each case, no "rational" method of locating the most significant entity in response to a given set of circumstances. The fundamental is embedded in detail, the general in the particular. A practitioner of one discipline cannot know and is unlikely to admit that the practitioners of another are better equipped to respond to a particular problem.[11] The key problem area, and the organizations to be responsible, must therefore be selected by a process of political barter.

Interaction between concepts, organizations and problems

Common features have been detected in the three types of complexity, but each type has nevertheless been treated as isolated from the others. This is not so. Organizational, conceptual and problem systems exist as aspects of one another. Change in one provokes change in the others. which therefore compounds the complexity.[2] These different interactions are not simultaneously recognized, since they are each the concern of different disciplines. New fields of knowledge are developed in response to new problems, and new organizations are established to facilitate regular activity with respect to new problems. But new fields of knowledge result in the detection of new problems, or organizations may be created to further interest in particular concepts, etc.

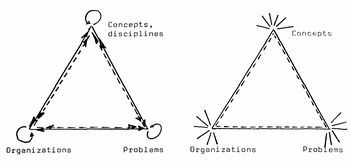

It is useful to distinguish an integrative interaction whereby, for example, inter-conceptual integration legitimates and eventually leads to inter-organizational integration. Similarly, a disintegrative interaction exists whereby, for example, decrease in inter-organization coordination leads to a decrease in the perceived inter-linking of problems. These interrelationships may be represented by Figure 1. The source of change is therefore very much a "chicken-and-the-egg" question.

In order to derive some measure of aspects of complexity in each case and the manner in which each aspect of the complexity is related to others, the following can be distinguished:

- number or population of entities

- variety, diversity or number of species of entities

- fragmentation or extent of within-species diversification

- interconnectedness, or decentralized inter-entity links or cooperation

- order, centralization or presence of hierarchies of dominance

- competition between entities.

Individual in relationship to complexity

Up to this point, it has been convenient to avoid reference to the individual, but clearly organizations and concepts are the productions of individuals, and problems are detected by individuals, and it is in terms of the individuals's powers of comprehension that complexity is defined. In addition, complexity experienced personally by individuals bears a close resemblance to that noted for organizations, concepts, and problems.

It is possible to speak of an increase in the number of roles (or equivalent psychological states) activated by or accessible to an individual. This growth is paralleled by a fragmentation and specialization of traditional roles. Accompanying these trends is an uncharted growth in the variety of possible roles and life-styles. These atomizing and complexifying trends are partially counter-balanced by efforts at formulating unifying philosophies or more integrated and mature life-styles.

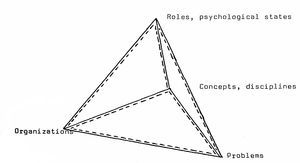

The individual psycho-system may therefore be added to Figure 1 to give Figure 2. [10] The integrative and disintegrative interactions may also be added.

| Figure 1. Indication of interrelationship between three types of psycho-social entity. Subject to 6 conditions of complexity (see Table 1) |

|

| Figure 2. Indication of interrelationship between four types of psycho-social entity |

|

| Table 1: Interactions between conditions of psycho-socialcomplexity for different groups of entities | Table 2: Limits in variation of measures of complexity for an entity in an ecological niche | ||||||||||||

|

| Organizations | Concepts | Problems | Roles | Maximum

| Minimum

| |||||||

| Number / Population | Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease | Increase Decrease | Increase Decrease | Information overload

| Insufficient stimuli

| |||||||

| Variety / Diversity

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Complexity

| Immaturity

| |||||||

| Fragmentation within species

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Inability to coordinate action

| Lack of specialized ability

| |||||||

| Inter-connectedness

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Inability to act

| Spastic action | |||||||

| Order/

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Overthrown by revolt

| Revolt

| |||||||

| Competition

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Increase Decrease

| Elimination

| Elimination

| |||||||

The question of personal identity, perceived complexity, fragmentation of the personality, and the ability to create stable psycho-social relationships (essential to peace) are all intimately related. R. D. Laing suggests that a firm sense of one's own autonomous identity is required in order that one may be related as one human being to another -- otherwise any and every relationship threatens the individual with loss of identity. Furthermore, the changes in the relationship between the different aspects of a person's relationships to himself affect his inter-personal relationships . [12] Marcuse suggests that psychological problems therefore turn into political problems, private disorder reflects more directly the disorder of the whole, and the cure of personal disorder depends more directly than before on the cure of general disorder. [13] Lawrence S. Kubie argues that unless the individual can free himself from internal tyranny he will restrict the freedom of his society to change.[14] Donald Schon notes that change in organizations has its impact on the person, because beliefs, values and the sense of self have their being in social systems.[2] Measures of complexity for the person can be envisaged and added to Table 1.

Table 1 provides a crude overview of the complexity with which society and the individual are faced. Increases or decreases in any measure cause changes in other parts of the system. It is doubtful whether universal agreement could be obtained on the interrelationships, even if more cells were introduced into the Table.

Since it is man who is directly or indirectly the major cause of change in the psycho-social environment, his individual actions may be considered the origin of the dynamic of the system. Faced with the different features of complexity noted above, he responds in a manner to ensure himself an adequate behavioural niche.[15] Some idea of the limits by which he is bounded is given in Table 2. His relationship to these limits may be modified by changes in his environment to the other measures noted in Table 1.

In carving out and developing an adequate behavioural niche in response to a changing environment and his own developmental needs, it may be assumed that each person adapts the condition of his own psycho-social system. These responses may be creative responses which modify the measures of complexity in his environment due to the formation of new organizations or concepts. It is not known why a given individual finds a given niche satisfactory, whereas another is motivated to seek a "better" one and will refuse to adapt to the existing environment. The dynamics of change would seem to originate in the individual's rejection of the conditions represented by a particular combination of measures of complexity such as those mentioned above. Some combinations of such measures may represent states in which identity is threatened for the personality type in question. Complexity may constitute a direct threat to identity. [12]

It. is possible that there are different strategies by which an individual can reinforce his identity as he develops. But basically, unless the individual can be placed in a more commanding positionwith respect to the information to which he is continuously exposed, he mill adapt or redefine himself and his habitat in such a way as to eliminate consideration of all information outside certain tolerance limits -- for with a threat to the stability of his environment it no longer provides an anchor for personal identity and a system of values. [2] He will set up his own "doll's house" model of relevant actors in his psycho-social environment.

Approach to complexity

Some idea of complexity in the psycho-social system has been given above. It is assumed here that the only useful collective decisions topromote peace must be made on the basis of some means of ordering complexity in a systematic manner -- or else run the risk of using simplistic models inadequate to the situations, on other than a short- term basis, and possibly counter-productive.

The task to be tackled parallels that in the case of natural environment systems described by David Pimentel in which there is a multiplicity of inter-specific "food chains", together with many branches and cross-connections among food chains making a structure of interactions called "food webs". The complexity of these food webs is such that no one has yet worked out the complete pattern of food relationships and interactions in any natural community. The relationships between 50 species in a given community results in a diagram "so full of lines that it is difficult to follow" and this only represents one quarter of the 210 known species in a "simple" community. [16] In such a situation a simplistic model used as a guide to the use of pesticides could be disastrous.

The approach advocated to penetrate complexity is to develop uses of an existing device which could handle and display the multiplicity of relationships in a manner to facilitate understanding. This is described in the next section.

In describing the device it is unnecessary to distinguish between the different types of entity or relationships making up the complexity. In each case the device is handling entities and relationships. Categorization of these features should be left to the user and not limit the flexibility with which data can be handled.

The advantages of this sort of approach have been argued elsewhere. Whether attention is focussed on organizations, concepts or problems, or even the components of natural eco-system, it is possible to distinguish relatively invariant continuing entities but only to the extent and in the field in which they each maintain two types of relationships -- internal ones to various sub-systems and structures and external ones which link them, either as a whole or via a sub- system, to their surrounds. The entity is in fact a pattern ofrelationships, subject to change but recognizably extended in time.

This way of regarding the objects of our attention helps to resolve the dichotomy between the Individual and society and many other pseudo- problems resulting from the tendency, built into language, to regard entities as "things", rather than systematically related sequences of events. [8,17]

This "loose" approach can be achieved by handling the entities and relationships as networks which can be processed and represented using graph theory techniques. [18] In effect, a non-quantitative topological structure of the psycho-social system is built up, to which dynamic and quantitative significance can be added as and when appropriate data becomes available.

Description of interactive graphic display technique

The suggestion has been made above that structuring the relationship between entities could best be accomplished using graph theory methods. There are four disadvantages to this approach:

- in matrix form, such structures cannot be visualized.

- graphic relationships are tiresome and time-consuming to draw (and are costly if budgeted as "art work").

- once drawn, there is a strong resistance to updating them (because of the previous point) and therefore they quickly become useless.

- when the graph is complex, multidimensional, and carries much information, it is difficult to draw satisfactorily in two dimensions. The mass of information cannot be filtered to highlight particular features -- unless yet another diagram is prepared.

These four difficulties can be overcome by making use of what is known as "interactive graphics". [19] This is basically a TV screen attached to a computer. The user sits at a keyboard in front of the screen and has at his disposal a light-pen (or some equivalent device) which allows him to point to elements of a network of entities displayed on the screen and instruct the computer to manipulate the structure in useful ways. In other words the user can interact with a representation of the network using the full power of the computer to take care of the drudgery of:

- drawing in neat lines

- making amendments

- displaying only part of the network so that one is not overloaded with "relevant" information

- storing labels and notes on particular features.

In effect the graphics device provides the user with a window or viewport onto the network of psycho-system entities. Ho can instruct the computer, via the keyboard, to

1. move the window to give him, effectively, a view onto a different part of the network -- another conceptual domain.

2. introduce a magnification so that he can examine (or "zoom in" on) some detailed sections of the network.

3. introduce diminuation so that he can gain an overall view of the structure of the entity domain in which he is interested.

4. introduce filters so that only certain types of relationships and entities are displayed -- either he can switch between models or he can impose restrictions on the relationships displayed within a model, i.e. he has a hierarchy of filters at his disposal.

5. modify parts of the network displayed to him by inserting or deleting entities and relationships. Security codes can be arranged so that (a) he can modify the display for his own immediate use without permanently affecting the basic store of data, (b) he can permanently modify features of the model for which he is a member of the responsible body, (c) and so on.

6. supply him with text on features of the network with which he is unfamiliar. If necessary he can split his viewpoint into two (or more) parts and have the parts of the network displayed in one (or more) part(s). He can then use the light-pen to point to each entity or relationship on which he wants a longer text description (e.g. the justifying argument for an entity or the mathematical function, if applicable, governing a relationship) and have it displayed in an adjoining viewport.

7. track along the relationships between one entity and the next by moving the viewport to focus on each new entity. In this way the user moves through a representation of "psycho-social space" with each move, changing the constellation of entities displayed and bringing new entities and relationships into view.

8. move up or down levels or "ladders of abstraction". The user can demand that the computer track the display (see point 7) between levels of abstraction, moving from sub-system to system at each move bringing into view the psycho-social context of the system displayed.

9. distinguish between entities and relationships on the basis of user-selected characteristics. The user can have the "relevant" (to him) entitiesdisplayedwith more prominent symbols and the relevant relationships with heavier lines.

10. select an alternative form of presentation. Some users may prefer block diagram flom charts to illustrate the relationship between entities, other may prefer a matrix display, others may prefer Venn diagrams, or "Venn spheres" in 3 dimensions, etc. These are all interconvertible (e.g. the Venn circles are computed taking each network node as a centre and giving a radius to include all the sub-branches of the network from that node.)

11. copy a particular display currently on the screen. A user may want to keep a personal record of parts of the network which are of interest to him. (He can either arrange for a dump onto a tape which can drive a graph plotter, a microfilm plotter, or copy onto a video-cassette, or obtain a direct photocopy.)

12. arrange for a simultaneous search through a coded microfilm to provide appropriate slide images or lengthy text which can in its turn be photocopied.

13. select significance of coordinate axes to order structure to highlight features of interest in terms of the chosen dimensions.

14. simulate a three-dimendional presentation of the network by introducing an extra coordinate axis.

15. rotate a three-dimensional structure (about the X or Y axis) in order to heighten the 3-D effect and obtain a better overall view "around" the structure.

16. simulate a four-dimensional presentation of the network by using various techniques for distinguishing entities and relationships (e.g. "flashing" relationships at frequencies corresponding to theirimportance in terms of the fourth dimension.)

17. change the speed at which the magnification from the viewport is modified as a particular structure is rotated.

18. simulate the consequences of various changes introduced by the user in terms of his conditions. This is particularly useful for cybernetic displays.

19. perform various graph or network analyses on particular parts of the network and display the results in a secondary viewport (e.g. the user might point a light-pen at an entity and request its centrality or request an indication of the inter-connectedness of a particular domain delimited with the light-pen.)

This is not the place to do more than outline some of the other present and future possibilities in this area. Video-cassette copies of syste-structures can be widely distributed and used for university or public TV documentaries on complex eco-systems. Microfilm and other plotters can beused to map largo and complex systems. Colour graphics unitssome up to 150 x 150 cm) are in use with the possibility of 512 colours (which allows even more information to be conveyed in one image). [20] Helmets fitted with display screens give the wearer the illusion of being able to move physically through computer projected spaces. Linked graphics terminals allow many users to work simultaneously on the same area of (semantic) space, thus augmenting the possibilities of face-to-face discussion. [21]

The current uses of such devices in chemical laboratories to visualize- atoms and their relationships are particularly suggestive of radical approaches to psycho-social system entities and their relationships which merit further study. For example, all the possible mays of constructing a specified chemical structure, are visualized given a set of specified passible starting sub-units and restrictions on ways they can be combined. [22] This could lead to ways of designing new institutions from a pool of organizational sub-units and personal skills, particularly organizations characterized by complex matrices of relationships rather than simple lines of authority. In another application, the potential field surrounding different types of atoms is mapped under different conditions and stored. [23] This could lead to mays of handling and visualizing psycho-social system entities in termsof field theories.

Graphics and communication

In order to understand the value of interactive computer graphics, a few basic principles of communication should be considered. Languages are used to convey thoughts. Languages may be gestural, verbal, written, notational, or graphic. The effectiveness of a language depends upon its ability to retain and transfer meaning and this in turn depends upon the complexity of the language. One can conceive of a spectrum of "language and medium" from primitive gestures through to sophisticated computer environments. At each point in the spectrumthere are disadvantages and advantages for communication. An attempt has been made to list these out in Figures 3 and 4 . [24] These should be considered as very tentative schemas only.

These Figures suggest that most of the advantages of the early portion of the spectrum are combined together in the later portions where interactive graphics is used in various ways. The question is why do graphics help to convey more information than words. One reason is that as concepts become more complex, they do not lend themselves to easy encapsulation in words and phrases. Often an explanation in simple words, whilst theoretically possible, can be achieved only at the price of such prolixity as to defeat the ends of the explanation. Many objects, processes, or abstractions can be portrayed for discussion using a few simple graphical symbols much more easily than can be described verbally (of the classic example of the spiral staircase). The other pressure is of course that many subtle invariant and relationships currently displayed in statistical tables, are ignored unless they can be represented in meaningful graphical form.

Figure 3: Comparison of different methods of communicating concepts

| Method

| Advantages

| Disadvantages |

| Gesture

| direct and to the point;

| no abstraction possible dramatic impact |

| Speech

| personalized, subtle, poetic, imageful, analogy-full, adjusted to audience

| no permanent record, meanings and models shift from phrase to phrase |

| Writing

| permanent record; words weighed and compared in context; document forms an intelligible whole

| meaning of words undefined or differ between documents; definitions become concretized and language dependent; complexity of abstractions limited by syntax of language; problem of jargon |

| Image

| provides context in physical terms; involving, highly complex, high information content, high interrelationship

| superficial and unstructured |

| Maths

| handles very complex abstractions and relations and a multiplicity of dimensions | loss of intuitive appreciation of the concepts involved; impenetrable without lengthy initiation; system of notation becomes more complex than the concepts described; impersonal |

| Diagram (exhibit charts)

| structured to make a specific point | over-simplification; exageration of some features at expense of others; processes only displayed statically |

| Artistic mobiles

| complex, new and unredictable relationhips

| experience primarily incommunicable |

| Diagram (flow charts/ graphs)

| portray all detectable interrelationships in precise manner; panoramic view of system

| visually complex to the point of impenetrability; processes still conveyed statically; difficult to modify |

| Method

| Advantages

| Disadvantage

|

| Interactiveqraphics (alphascope)

| precise messages; responsive; contents cum be) oriented to suit user

| no structured overview; bounded by language modeof program; processes conveyed as a sequence of isolated messages (or asa qame experience)

|

| Psychedelicenviron-ment

| very subtle and complex imagery and relationships; process oriented; integration of visual and audio; psychologically involving

| no scientific content; no significant invariants; experience primarily incommunicable

|

| Interactivegraphics (structured image)

| greater user selectivity and control on content and form of presentation; complex abstractions held on display; processes displayed as flows; dynamic; enhanced creativity; 2-4 dimensions.

| highly structured without the subtle relationships characteristic of arts; user still centred "outside" the structure "looking in"

|

| Computer graphics art

| generation of new and unpredictable dynamic imagery

| no scientific or "real world" predictive value

|

| Interactive graphics (multiterminal ) Interactive graphics (coloured and image)

| teams working simultaneously on same ideas; access to each others "semantic space"; interactive thinking higher information content; visually more intriguing; closer to artistic media; more powerful presentation of processes

| fundamental distinction remains between artistic use of the display or surface volume and scientific interest in structure and data base; still only reflects a portion of the subtleties, of all invariants and processes known to psychologists, diplomats, etc.

|

| Interactive graphics (3D helmet)

| user psychologically centred within the structure

|

|

| Interactive ideograph(hypothetical)

| continuous gradation and interaction between scientifically structured and aesthetically structured display; enhanced creativity; reflectssubtleties of psycho-logists, diplomata, etc.ableto convert to andfrom a"field theory"presentation of structures

| still only a scaffolding for disciplined thought

|

Some current interactive graphics uses include, for example, calculation and analysis of electronic circuits, design of aerodynamic shapes and other mechanical pieces, design of optical systems and plasma chambers, simulation of prototype aircraft and rocket flight, visualization of complex molecules in 3 dimensions, air traffic control, chemical plant control, factory design and space allocation, project control, primary, secondary and university education and educational simulations.

In every case above there is some notion of geometry and space, but the geometry is always the three-dimensional conventional space. There is no reason why "non-physical spaces" should not be displayed instead and this is the domain of topology. The argument has been developed by Dean Brown and Joan Lewis. [25]

It is useful to introduce C. S. Peirce's term "iconic", namely "a diagram ought to be as iconic as possible, that is, it should represent (logical) relations be visible relations analogous to them".[26] Iconics is therefore connected with the degree to which features of the graphics display contribute towards, or facilitate understanding. Patrick Meredith makes similar points in discussing the uses of "semantic matrices". [27] He contends that grammarians have attended exclusively to the linear arrangement of words in sentences but that this conventional grammar must now be regarded as a particular case of a very much more extensive "geometrical syntax", just as Aristotelian logic turned out to be a special case of a much wider system of symbolic logic -- and that in the spatial arrangements of entities, their geometric relations should be correlated with the logical relations between them. He gives the periodic table of chemical elements as an example of the richness of the field to be explored. The power of this two-dimensional visual display in generating systematic references concerning relations between its constituents indicates the latent potentiality of the mascent geometrical syntax.

There is however a question of "iconicity for whom". A well-known survey by Anne Rowe (The Making of the Scientist) found a high correlation between (1) visual imagery and experimental inclination, (2) nonvisual imagery and preference for theoretical science. Many theoretical scientists prefer not to use visual imagery -- which may explain their difficulty in communicating with other sectors of society. Don Fabun draws attention to the possibility that non-Americans may not find the display of concepts and their relations by grids or network structures very meaningful. Europeans, and particularly Orientals, are inclined to attach importance to areas. There does not seem to be muchextensive work on this guestion cross-culturally or with respect to different personality types. And yet, it may strongly influence the manner in which concepts are communicated, particularly if certain personality typos tend to be associated with certain disciplines.

Progress in understanding is made through the development of mental models or symbolic notations that permit a simple representation of a mass of complexities not previously understood. There is nothing new in the use of models to represent psycho-social abstractions. Jay Forrester, making this same point with respect to social systems, argues however that every person in his private life and in his community life uses models for decision-making. The mental image of the world around one, carried in each individual's head, is a model. One does not have a family, a business, a city, a government, or a country in his head. He has only selected concepts and relationships which he uses to represent the real system. But when the pieces of the system have been assembled, the mind is nearly useless for anticipating the dynamic behaviour that the system implies. Here the computer is ideal. It mill trace the interactions of any specified set of relationships. The mental model is fuzzy. It is incomplete. It is imprecisely stated. Furthermore, even within one individual, the mental model changes with time and with the flow of conversation. Even as a single topic is being discussed, each participant in a conversation is using a different mental model through which to interpret the subject. And it is not surprising that consensus leads to actionswhich produce unintended results. Fundamental assumptions differ but are never brought out into the open. [28]

These structured models have to be applied to any serially ordered data in card files, computer printout or reference books to make sense of that data. Is there any reason why these invisible structural models should not be visible to clarify differences and build a more comprehensive visible model? The greater the complexity, however, the more difficult it is to use mental models. 'For example, in discussing his examination of an electronic circuit diagram, Ivan Sutherland writes:

"Unfortunately, my abstract model tends to fade out when I get a circuit that is a little bit too complex. I can't remember what is happening in one place long enough to see what is going to happen somewhere else. My model evaporates. If I could somehow represent that abstract model in the computer to see a circuit in animation, my abstraction wouldn't evaporate. I could take the vague notion that "fades out at the edges" and solidify it. I could analyze bigger circuits. In all fields there are such abstractions. We haven't yet made any use of the computer's capability to "firm up" these abstractions. The scientist of today is limited by his pencil and paper and mind. He can draw abstractions, or he can tothink about them. If he draws them, they will be static, and if he just visualizes them they won't have very good mathematical properties and will fade out. With a computer, we could give him a great deal more. We could give him drawings that move, drawings in three or four dimensions which ho can rotate, and drawings with great mathematical accuracy. We could let him work with them in a may that he has never been able to do before. I think that really big gains in the substantive scientific areas are going to came when somebody invents new abstractions which can only be represented in computer graphical form." [29]

The primary function of visual representation is to facilitate understanding. To understand a concept is to apprehend correctly all the relations which determine its structure. This means not only grasping the fact that certain relations hold between certain entities but also seeing that the nature of the entities permits those relations to hold and that the global character of the concept determines their occurrence. [27]

Use of information

The implication to this point has been that what is required is more powerful research insight into the different types of organized complexity. This is in fact totally insufficient. Research information systems are used by research workers and tend to be of little significance, directly or indirectly, to non-research areas -- particularly in the social sciences. How exclusive should an information system be?

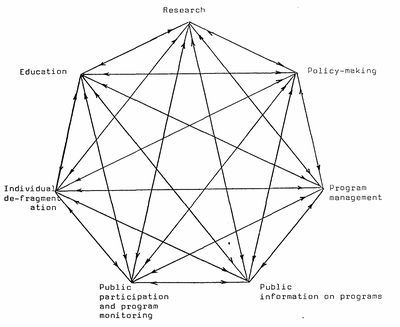

A means needs to be found of making the type of information discussed here directly accessible to the following information users:

- research workers

- education of students, briefing of diplomats, etc. policy-making

- program management. [30]

Non-research needs tend to be viewed with a certain contempt by research workers, but this is merely the counterpart to the contempt in which research conclusions are held by those involved in day-by-day decision-making. [31] This antipathy arises from the tendency of researchworkers to focus on problems which decision-makers consider irrelevant and to publish their results in an incomprehensible form, and the tendency of decision-makers to use techniques and models which research workers consider antiquated and to focus on symptoms rather than causes of problems.

But even a sophisticated alliance between research and decision-making is totally insufficient. Students must be educated about the psycho- social system -- and this education should be based on the same data used for research and decision-making and not on antiquated simplifications .

Educating students is educating the (relatively) powerless. Even this complex of users is inadequate to break the dangerous situation now predicted for the very near Future (if not in many ways already a reality), namely that the politician, working in tandem with his technological advisors and program designers, is increasingly in a position to put forward interpretations of urban or world "reality", programs to deal with it and evaluations of those programs as implemented, based on knowledge either unavailable to those who might challenge him or unavailable at the time that a challenge might be most effective. [32]

In other words, it would be extremely irresponsible to create a sophisticated tool for a system which will use it to strengthen its own position at the expense of its environment. As Herman Kahn points out, we now face the sinister situation in which the world is becoming so complex and changing so rapidly and dangerously and the need for anticipating problems is so great, that we may be tempted to sacrifice (or may not be able to afford) democratic political processes. [33] Faced with this threat, it might be better to suppress initiatives to produce such a weapon against the powerless and to bank on the protective advantages of complexity. This is the dilemma: either one opts for inaction in the belief that the misuse of science and technology will breed its own compensating mechanisms and possibly the decay of the system -- or else one banks on the advantages which would accrue from a wider availability of such a tool.

In terms of the second option, there are three other necessary sets of users:

- public information on system modifications

- public monitoring of system modifications including privacy protection and participative action

- use by the individual to de-fragment himself.

The first two deal with means of updating weak links in the democratic process. The third concerns private use by the individual to straights out or order his own mental models of his environment. There may be others.

These seven uses should, ideally, be interrelated (see Figure 4) via 2 common data base and the much discussed data networks. Each requires different techniques of data presentation, filtering and manipulation for which the visual display unit is ideally suited. Insights and problems detected in one use should affect the priorities of other uses The current tendency is however to build separate information systemsof different levels of sophistication for each use, so that they are quickly out of phase, incompatible and in many cases inadequate and useless.

| Figure 4. Interrelationship between different uses of information, which should ideally be based on a common data-base to avoid spastic change in society |

|

In such circumstances, developments in each area do not reinforce and counter-balance one another, rather the psycho-social system evolves in leaps and starts. Information systems constitute the nervous system of planetary society. The fragmented approach to their design and use would seem to lead directly to social crises analoqous to those found in the case of certain disorders of the nervous system, as though the psycho-social system was some organizational dinosaur suffering from spastic paralysis and aphasia.34 Integrated and harmonious development can only be achieved if the information system is designed for multipurpose use -- and especially by those with resource problems, as in the developing countries and in the decayed areas of developed countries.

If the different systems cannot be interrelated, it mould be preferable as a strategy to make the visual display technique available only as an idea clarification and concept integration aid, and block its systematic use for the penetration of organized complexity. (This may be easy since most organizations have a natural horror of having their detailed structure exposed to others -- despite their own interest in that of others.)

Relevance to peace

The interactive graphics technique provides a means of handling complexity. The question now is: in what way does this contribute specifically to the knowledge and value requirements for peace. To some "complexity" is a guarantee of peace. Johan Galtung suggests a general formula for peace based on increasing the world entropy, i.e. increasing the disorder, messiness, randomness, and unpredictability by avoiding the clear-cut, the simplistic blue-print and excessive order. [35] There is a distinction however between a degree of complexity which produces overload, and irrational and uncoordinated responses, and that which requires many known relationships to be taken into account. Complexity may provide peaceful behavioural niches which act as protective bulkheads. Without a clearer picture, however, it is impossible to determine whether the protection is adequate or equivalent to sheltering in dense dry undergrowth from an approaching bush fire.

The problem is how to lower the degree of complexity, but at the same time to beware of simplistic proposals for change by those who believe they have an adequate model of the complexity.

The notion of a peaceful society has come to resemble the mythical, calm "stable state" noted by Donald Schon which is to be reached after a time of troubles. He suggests that belief in it is a belief in the unchangeability, the constancy of central aspects of our lives, or belief that we can attain such a constancy. This belief is institutionalized in every social domain, in spite of acceptance and approval of change and dynamism. It is a bulwark against the threat of uncertainty and instability. Given the roulity of change, the belief is only maintained through tactics of which me are largely unconscious so that our responses am spasmodic responses of desperation and largely destructive. He is concerned with developing institutional structures and ways of knowing for the process of change itself i.e. "beyond the stable state". Current proposals to institutionalize stability are generally efforts at restoring the institutional status quo ante which is identified as the best approximation to the stable state.

The problem of peace is therefore not so much one of producing a new formula for combining existing organizational building blocks. This could only result in another unsuccessful compromise in a long series. There is no evidence that the insight is available to design a peaceful society in which systematic violence is absent. There have been many proposals, but there is no evidence. We have no reason to assume that political societies will prove to be regulable at any level which me would regard as acceptable. Many species have perished in ecological traps of their own devising. We may already have passed the point of no return on the road to some such abyss.8 As an example, a test experiment could be envisaged in which a "peaceful community" is designed and set into operation with all the resources and disciplinary skills available - there is a high probability of failure within one generation or at least the introduction of rules which do violence to the original values in terms of which the community was designed. As evidence for this one may note the failure rate of communes, the second generation problem of kibbutzim, the urban disaster constituted by "planned" communities, and the difficulties associated with harmonizing relations in an isolated group of people over time periods exceeding a few days. The probability of failure increases with the diversity of psychological types, interests and cultures represented. Proposers benefit from the fact that by definition they cannot produce evidence for the success of their proposal and it is probable that they will not be there when it bears its fruits.

One reason why it is difficult to design a society is that the model used is by definition not sufficiently complex or detailed to take account of all the loose ends which will emerge and cause friction leading to violence. It is difficult to build up a picture of the dynamic interactive effects of sub-sections of the model. Most difficult of all is taking into account the individual as a developing, creative, and as such essentially unpredictable, entity for which we know our models are inadequate.

For the above reasons, it seems Useful to suggest that peace is an ecological problem, namely a problem of harmonizing the interrelationships in society between a developing individual and his evolving environment. It is instructive to use the insights concerning the less ambiguous natural environment ecology (with respect to which we are objective), to draw attention to problems and opportunities in connection with the psycho-social environment ecology within which we are thoroughly embedded.

Peace is here conceived less as a state and more as a very complex evolving set of relationships in which the latter bear some harmonious relationship to one another. The two key questions are: evolving towhat, and what is harmonious. As in the case of the natural environment, there is no immediate answer to these questions -- there is insufficient understanding of the relationships and the nature of psycho-social development. Simplistic proposals for change and control may be assumed to bear the same relationship to the failure of the psycho-social eco-system as do pesticides to the failure of the natural eco-system. The psycho-social system will resist "redesign" but it is as yet impossible to say when the resistance is beneficial and when it is unfortunate and to be overcome.

The general problem of psycho-social ecology may be considered in terms of the different types of ecology mentioned in an earlier section, namely:

- organizational ecology i.e. the harmonious evolving interrelationships between organizational units

- conceptual ecology i.e. the harmonious evolving inter-relationships between theoretical formulations, value and belief systems

- problem ecology i.e. the harmonious evolving inter-relationship between problems

- psycho-ecology or psycho-dynamics i.e. the harmonious evolving inter-relationships within a person's psyche.

In each case, if one uses primitive models for a complex eco-system, many discontinuities will appear. If one organizes or reifies in terms of the primitive models, then such discontinuities will take the form of violence -- whether physical or structural. The system will be spastic. [34]

Peace and inequality

The parallel between the natural and the psycho-social ecology is, of course, debatable, but even if accepted with reservations, it raises the difficulty of the status and function of violence. In a natural environment destructive violence is a necessary feature of inter-specific relationships, and non-destructive conflict is a necessary feature of intra-specific territorial behaviour. It goes against all our value systems to suggest that destructive violence is a natural feature of the psycho-social environment, despite an almost incredible amount of evidence to the contrary.

The argument is that man, as part of the natural environment, is the only animal to engage in systematic destruction of its own kind -- and therefore that this is not natural and, in a peaceful world, should cease. It is possible however that a clearer insight into psycho-social relationships mill eventually highlight a different picture.

Through progressive alienation from the natural environment, man may have redefined and substituted his psycho-social environment as a new kind of natural environment. This environment, as so defined, is perceived as populated by not one but many psycho-social species -- possibly to provide and canalize the dynamics of the system. This suggestion of a multiplicity of different species of psycho- social man also goes completely against all our value systems. "All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights". Again there is an incredible amount of evidence that the concept of equality is not about to be considered of great moment. "The hierarchy of industrial roles distributes authority between our mould-be equal selves at least as unequally, and sometimes less acceptably, than did the status structure of traditional society.... me are almost wholly ignorant of human variation, whether biological, psychological, or cultural, and our entrenched misconceptions of equality prevent us from using even such knowledge as we have. We are seeing only the first stirrings of that respect for human difference on which an adequate concept of equality may some day be based." [8]

Suppose however that, as a more complex model of the situation, people are equal in terms of potentiality (and, ideally, before the law) but unequal in terms of actuality. And furthermore, that the probability of realizing the full potential decreases with age and the difference between individuals incseases with age. (To avoid misinterpretation, it is important to understand that the equality and inequality refers to psycho-social features which are considered to be totally independent of any superficial racial characteristics.) It might then be possible to speak of a multiplicity of species, although it is not yet clear how species might be defined. Perhaps as a very first approximation to establish probable species differences between two roles, [37] some measure of the "non-fruitfulness" of any verbal (or other non-sexual) intercourse between them couldbe used.

Once verbal intercourse is non-fruitful, inter-specific interaction is possible in eight modes: neutralism, competition, mutualism, protocooperation, commensalism, amensalism, parasitism and predation.[38] Some of these may take the form of destructive violence which is justifiable in terms of the dynamics of the system of which both parties are members.

The top-dog/under-dog dominance relationship in social systems [39] could seem to be another form, cutting across some of the above modes. The pattern of all modes splits the community of species into levels equivalent to the trophic levels and food chains in natural eco-systems. The number of successive steps in a food chain is small being restricted by the ecological efficiency of the process of energy transfer between each step and by questions of metabolic rate and body size.

A focus on the specific objective of eliminating violence may be rather similar in feasibility and value to the attempt to eliminate violence from a natural eco-system such as a fish pond, a tropical jungle or game covered tropical grasslands. The only hope of achieving this is to place each animal in a cage. This eliminates the physical violence by substituting a form of structural violence. Unless a synthetic food supply is found, one is committed to undertaking the physical violence as zoo keeper or else the animals will die or revolt. Maximizing law and order does not eliminate violence, it simply relocates it in another part of the system.

It would be interesting to compare energy chains in psycho-social systems against food chains in natural systems and see whether similar relationships hold as is suggested by R. Margalef.[37] He suggests that it is possible to measure the "maturity" of an eco-system as closely related in one respect to its diversity or complexity and in another to the amount of information that can be maintained with a definite spending of potential energy. A highly diversified community has the capacity for carrying a high amount of organizations or information and requires relatively less energy to maintain it. Of particular significance for approaches to "peace", is that the necessay energy to disrupt an eco-system is related to 'its maturity -- anything that keeps an eco-system oscillating (or "spastic"), retains it in a state of low maturity. (It would be interesting to compare the crime rate with a measure of psycho-social system diversity.)

Dominance in social systems provides a situation with a tremendous potential for structural violence. [39] But dominance and diversity in natural systems form an area of complex and often obscure relationships not subject to neat, unitary formulations. [40]

A possible relationship to maturity is suggested by the hypothesis that local species diversity is directly related to the efficiency with which predators prevent the monopolization of the major environmental requisites by one species. In testing this, removal of the top carnivore reduced system diversity from 15 to 8 species. [41]

The problem in applying these insights to psycho-social systems is that top-dogs and selective violence may help to maintain the maturity of the system and increase the efficiency of utilization of resources.

This raises the question of what in Geological terms should bo maximized in psycho-social systems in order to approach the conditions represented by "peace". At this stage, too little is known about the energetics of such systems for useful decisions to be taken - plus the fact that change decisions are within-system mutations of specific entities which must then function in relation to the ecosystemic community of species. As such they cannot completely control the system.

Peace and the myth of man the individual

The suggestion in the previous section appears to bear some similarity to discredited theories of social evolution or "Social Darwinism".[43] These theories mere rejected because of their many racial and class implications. The latter arose from the implication of "once-an- underdog-always-an-underdog" because the evolutionary unit was assumed to be the individual. The suggestion here, however, is that the evolutionary unit is the role in the psycho-social system.

It is through a multiplicity of roles that an individual may participate simultaneously at many different levels (as top-dog, under-dog, etc.) in any of the energy chains in the system. Each role has a certain probability of being activated at a particular point in time. Only the roles are participants, however, never the undivided individual. The locus of identity or individuality may be assumed to be extrasystemic at some hyperspace position at the "centre of gravity" of the role complex. The integration of roles is currently of such little general interest that the individual as a whole human being may be considered as an abstract, if not already mythical, concept.

Because individuals are fragmented in the psycho-social system into roles of different levels of sophistication, the dynamic of the psycho- social system is essentially the projection, aggregation, interaction and concretization of the inter-role dynamics within each individual. Each individual develops role species forming an eco-system in which inter-species conflict at many levels within himself is the norm. This cannot be eliminated except possibly by evolving each such system into states about which little is as yet known -- the lion in the individual can only be made to lie down with the lamb under rather special circumstances. Nor can it be bottled up inside the individual who wants to see a reflection of his internal eco-system, however violent, in the psycho-social environment -- circuses and television, whilst feeding the growth of the desire, are in the long run unable to satisfy and contain it.

It may well be that, until men can individually achieve a "peace of mind" for themselves, countering their psychological fragmentation and loss of identity, there will be no peace. The violence which is deplored is due to healthy attempts, often misguided, to attain such a peace of mind within an impenetrable and twisted context which forces each man to treat his neighbour as a throat. The attempts are misguided because practically zero effort is made to guide the individualin the improvement of the quality of his psychological life -- to thepoint of ignoring it as 'subjective'. The "quality of life" aspect of the environment issue, and the social aspects of development, for example, are confined at governmental level to matters of physical well-being or else surface for consideration as mental illness. (UNESCO's views on the non-economic aspects of development, were not incorporated into the program for the 2nd United Nations Development Decade.)

Peace in the world is therefore not simply a matter of juggling with the objective features of the psycho-social system -- organizations, concepts, problems. Unless each person's psycho-ecology becomes less spastic and more integrated; all objective measures will be unstable and of short duration. As the Constitution of UNESCO puts it "since wars begin in the minds of man, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed....a peace based exclusively upon the political and economic arrangements of governments mould not be a peace which could secure the unanimous, lasting and sincere support of the peoples of the world".

Inter-specific conflict will continue to lead to violence to the human person -- as a necessary controlling process in the psycho-social system -- for as long as individuals are encouraged or forced to identify themselves and others with the roles by which they participate in the sub-system in question. The dynamics of the psycho-social system require the destruction of some roles and relationships to protect and further the growth of others. In other words, individuals are currently obliged to find their identity in what is scheduled for destruction. Currently this destruction is often liteally done over someone's dead body because of the attachment and commitment of the individual to the role and the organizations which constituted its habitat. The role, the individual and his body are perceived as an amalgam -- any change or evolution must therefore result in violence to the body.

This is particularly important in the case of social structures such as organizations. These are the concretization of behaviour patterns and abstract relationships. Because the latter are more ambiguous and less visible, the identification is with the visible (often literally "concrete") features of the organization. Change is blacked because the relationships are identified with physical features whose physical relationships cannot be flexibly or continually developed. Emotion and energy ideally available for system transformation go into system maintenance.

If transformations cannot be accomplished "from the outside" by hygienic, transcendental interference in system processes. The remaining possibility is to take the psycho-social system seriously and deliberately "evolve" it -- evolution becomes internalized, conscious and self-directing as suggested by Julian Huxley. [44] It ishowever more a question of catalyzing its evolution as a learning system than of developing it in terms of some central policy. The catalyzers must go 'meta' with respect to the discovered systems, prodding them to develop evaluative processes conducive to learning, and linking them in learning networks. [2]

The problem of this evolution is determining what is to be maximized -- but this in itself is part of the learning process. Biologists have tried and discarded many definitions of biological progress -- Kenneth Boulding considers that what evolves in some sort of information or improbability of structure whether in natural or psycho-social systems. Perhaps the answer is to be found in a strategy common to development, evolution and permanent revolution39 possibly, following Margalef's approach, the growth of total maturity (GTM), conceived in dynamic psycho-social terms, and as a generalization of GNP.

To approximate progressively to the most appropriate strategy, peace must be treated as a four-fold ecological problem -- not a matter of designing new organizational dinosaurs as memorials to non-critical problems. (Ashby's Law of Requisite Variety states that the variety or complexity of a given situation can only be dominated adequately by using strategies having at least as great a capacity to generate varietythemselves -- simplistic models do not have this.) It requires a far more sophisticated appreciation of the variety and complexity of the entities in the psycho-social system and their inter-relationships. This appreciation can only be widely provided by using a more powerful means of information handling and presentation. The visual display technique offers a means of supplying a dynamic visual representation of the knowable complex psycho-social relationships. This representation is intermediate between the abstract and the concrete. Once the psychological center of gravity is shifted from the concrete to the visualized relationships, system self-transformation can take place without physical violence.

Values

The multiplicity of species making up the psycho-social system leads to a multiplicity of value systems -- to the point where each species may be expected to have its own value system. The suggestion is that it should be possible to extract common elements and formulate a set of universal values -- plus occasionally the implication that this could be a useful foundation for thinking about a world government.

There is undoubtedly no insurmountable difficulty in getting together people with similar perspectives and producing a set of values. The problem is whether these are of relevance and significance to those who did not participate in their formulation or whether they will merely irritate and stimulate counter value production. Values are formulated in response to experience which may have been modified in the time for a new set of values to permeate to the "distant" points of the psycho-social system.

One aspect of the thrust for a unified set of values is to provide society or government with guidelines for decision -- society is seen as a giant rational "decider" whose decisions are communicated and implemented. This center-periphery model ignores the insights of those studying social change which show that: the innovation evolves during the diffusion process; there is generally a plurality of sources formulating related and reinforcing innovations; and the innovation must usually be intermeshed with new needs comparable in force to the dynamic conservatism of the established system. [2] If organizations and society are treated as learning systems, the relationships between the formulations and those who are supposed to subscribe to them becomes much more subtle. In fact it is more useful to think of the psycho-social system as a value generating system -- in which values are generated at all points as a result of experience and interaction with the past values which have diffused to those points.

A more fundamental criticism of any attempt to generate a universal set of values is the implication that this would in some way supply the answer to society's troubles. If the psycho-social system is a value generating system, then any one set (which would be rapidly institutionalized) would be a stultifying constraint and a block on creativity -- there would be nothing more to be said, and the evolution of new values would cease or be viewed as disturbing the status quo. New circumstances, requiring modified values, would catch the psycho- social system by surprise -- unless a "value pool" was available. Differences, fragmentation and complexity arise within the psycho- social system to provide behavioural niches which protect variety and provide resources to keep the system as a whole viable in response to any crises.

An interesting study has been made which indicates the probable difficulty, if not the impossibility, of arriving at a universal set of values. W. T. Jones suggests that at the base of every personality, there is a set of pre-rational temperamental biases which are reflected in an individual's (or a society's) aesthetic and theoretical productions and his value preferences. He suggests the following (non-exhaustive) list of axes of bias along each of which individuals will tend to position their value preferences:

1. Order/Disorder: range between a strong preference for fluidity, muddle and chaos and a strong preference for system, structure and conceptual clarity;

2. Static/Dynamic: range between a strong preference for the changeless and eternal, and a preference for movement and for explanation in genetic and process terms;

3. Continuity/Discrete: range between a strong preference for wholeness or unity, and a preference for discreteness, and plurality or diversity;

4. Innter/Outer: range between a strong preference to "get inside" the objects of one's experience and experience them as one experiences oneself, and the preference for a relatively external relation to them;

5. Sharp focus/Soft focus: range between a strong preference for clear and direct experiences, and a preference for threshhold experiences which are felt to be saturated with more meaning than is immediately present;

6. This world/Other world: range between a strong preference for belief in the spatio-temporal world as self-explanatory, and a preference for belief that it is not self-explanatory. Alternatively a contentement with the here-and-now as opposed to a focus on other- time and other-place.

7. Spontaneity/Process: range between a strong preference for chance; freedom, accident or creative evolution, and a preference for explanations subject to laws and definable processes.

Jones points out that in the long run every particular theory will have limited appeal. It will structure experience satisfactorily only for those whose range of biases is approximately the same as that of the framer of the theory. This should also hold for value preferences. (Such biases may be at the base of choice of lifestyle, discipline preference, and mode of action -- experimental, methodological, theoretical -- within a discipline. They may determine preferences for the manner -- graphic or otherwise -- in which new information is presented for optimum understanding. They may carve up the psycho- social universe into major sectors within which certain role species are characteristic -- communication between such sectors is poor and values travel badly. This feature may protect essential psycho-social variety by affecting a role's tolerance to particular combinations of limits in Table 2.)

In a dynamic psycho-social system, any emergence of invariants which tend to change the balance of biases represented is likely to excite production of counter-actants. One reason is that the predominance of one value system may tend to reduce value diversity which is probably of importantepsycho-social survival value. The proponents and opponents of a universal set of values, and even of emphasis on abstractions such as "peace" and "values", are embedded in homeo- static psycho-social processes.

In these circumstances, it mould seem that a significant "within-system" proposal for a set of values is

1. the maximization of production of new improved values -- by continually exposing people to weaknesses in existing values. This would ensure refinement and clarification of the "conventional" values represented by the terms absence of violence, social justice, etc. and avoid any "hardening-of-the-values". An ideal society might be one in which value generation was maximized.

2. maximize the rate at which individuals are exposed to situations in which the consequences of their values are represented so that they can realize the need for improving them and then be shown alternative versions of such improvements, etc., until they will accept no further improvement;

3. maximize the dynamic maturity in the psycho-social system namely the generation of many species of entity with a high degree of interdependence.

Knowledge

A major theme of this paper is that it is not more knowledge of the same type that is needed, but new types of knowledge. Much of the complexity and information overload is due to excessive production of unintegrated knowledge. It is useful to think of researchers producing knowledge which decays rapidly into pellets of information unless revivified -- knowledge is integration of unrelated bits of information; documents represent fossilized knowledge, which can be reprocessed. What is required is knowledge which will help to reduce the decay rate dramatically and to "revivify" information. The remark of a Fortune editorial that "because our strength is derived from the fragmented mode of our knowledge and action, we are relatively helpless when we try to deal intelligently with such unities as a city, an estaury's ecology or "the quality of life"" (Fortune, February 1970, p. 92) is applicable to the psycho-social system as a whole.

The "hidden dimension" which must be faced is that of the degree of integration of the knowledge used across conventional discipline boundaries and across boundaries between various modes of thought and action (e.g. research, policy-making, education, etc.). Just as translations between natural languages is theoretically impossible but practically feasible to a satisfactory degree, so the attitude towards the interrelation of knowledge arising from different disciplinary perspectives should bo viewed as partially feasible in practice, even if no theoretical framework can legitimate it.

Clearly, the momentum of the knowledge producers and their organizational settings makes dramatic change almost impossible. The solution advocated here is therefore the provision of a device for them which is structured to facilitate integration of information and enhaces creativitiy and production of more integrative knowledge. In contrast, existing information systems encourage fragmentation and the generation of vast quantities of indigestible information.

With such a device, much vital existing information on isolated entities and processes in the psycho-social system can be "hooked together" in a manner which facilitates understanding by many disciplines simultaneously, and can highlight significant areas for research and action. Such an approach is vital to avoid clumsy spastic approaches to rectifying current problems. War and violence are the ultimate processes in a spastic society.

Our difficulty is that our mental models of psycho-social structure are based on patterns of relationships which are too intimately identified and associated with (visible) physical and behavioural structures which do not develop naturally and continually but can however (almost literally) be labelled. Means are required to increase reliance on more subtle and dynamic patterns of relationships for which more sophisticated methods of display are required.

Conclusion

The world crisis may be viewed as the closing of an ecological trap, in the multiple sense elaborated here, and as a failure of communication between governments and governed, between disciplines, between organizations, between generations, and between psychological states. It is not a matter of improving the technical means by which new information is generated or transferred from A to B, indeed it is this which is setting the pace. It is in the processes of interpretation, integration and comprehension that the problem lies.8 It is useless to step up the bombardement of the human organism by pellets of information and unrelated, "useful" but mutually antagonistic concepts unless the pellets are so organized as to be capable of faster assimilation. [27]

This integation must extend to the systems of interpretation by which alone communications have meaning and enable human beings to influence one another -- it is in this domain that coherence and continuity havealmost completely been lost. But in order to re-integrate what is being so explosively torn apart, it is necessary to look at the psycho-social system in its currently fragmented state -- this poses much subtler problems of communication for which the device described here may be of major significance.

Each entity in the psycho-social system must be "recognized" as it iscurrently fragmented, because in this state each fragment has its own relations with other parts of the system which we must necessarily comprehend. They have emerged into existence as relative invariants, for some other part of the system, in response to system conditions which must be understood before attempting any premature integration back into "natural wholes" -- and before using models which assume the existence of such integrated wholes or which deny the significance of some entities or relationships. In particular it may be an advantage to attack the myth of society as a unified whole and the myth of man the individual -- before establishing well-founded bases for any such beliefs.

To clarify the two myths, a new "Origin of Species" [43] is required to showhow and in what way each psycho-social system species arose and how it relates to other species. The only unity to be hoped for at this stage is an eco-systemic unity -- not some Utopian community of man.