|

by Judy Wickens, Union of International Associations, UIA

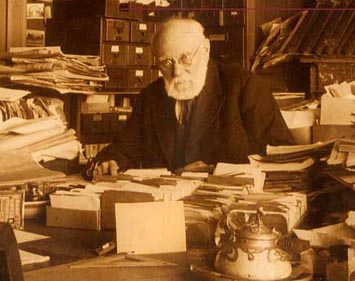

Paul Otlet. Some ideas are so bright that technology takes decades to catch up with them. This is true of the conception by Paul Otlet of a collection of all the information in the world in one place, which would be made accessible to any user while he sat at his own desk.

In an amazing leap of imagination, Otlet and his associate Henri La Fontaine – both Belgians – envisaged that one would work at an empty table and, by means of a kind of telescope, one would be able to consult any book situated in a central library. Sounds like the internet? Well, yes, but Otlet envisaged this in the early 1900s, and the web of computers which allowed the creation of the internet and its instant dissemination of knowledge would not be invented for much more than half a century.

Otlet was a lawyer, but his vision and passion were the assembling of knowledge and making it available to everyone who needed it, effectively the origins of information science, and this occupied his mind more than the practice of law. He wrote many articles, such as the letter to the Belgian Society of Sociology in 1908 which set out his thoughts.

Against a background of some recent international conferences intended to discuss world peace and a slow increase in the foundation of cross-national organisations, Otlet developed his theory that a wider availability of knowledge would promote international life, and that harmony would result: he even thought that a grouping of European states was not enough, countries of the entire world should be involved.

Paul Otlet looked for an international movement based not on territorial empires, politics or religions, or social classes, but on ideas and sharing the thoughts and intellectual inspiration produced by human effort. He proposed (my translation) 'in a material sense, the development of a vast network of means of communication which would facilitate the circulation of people, products and intellectual ideas' and 'the means of exchanging and communicating ideas so that it would be possible for everyone to know of everything in existence and everything which happened everywhere'.

In addition to an international documentation service, his project went even further than we have managed so far, a century later, as he called for an international language and the unification of methods and measurement systems which would permit immediate comparison of results.

For every branch of knowledge he called for the international federation of national associations in order to gather all available information and integrate it into one whole which could then be used for further expansion, and for the establishment of specified goals of international public interest. In 1905 Otlet and La Fontaine were the directors-general of the International Bibliographical Institute, and in 1908 they, together with Cyrille Van Overbergh, were Secretaries-General of the Central Bureau of International Associations, which organised in 1910 the first World Congress of International Associations, held in Brussels.

The Bureau and Congress led directly to the formation of the Union of International Associations, which continues to this day its huge and diligent task of documenting international civil society. The second Congress took place in 1913 but the third, planned for 1915 in San Francisco was delayed by the outbreak of the Great War and did not take place until 1920, in Brussels. Until the end of his life in 1944, Otlet persevered with his work on the promotion and expansion of knowledge by the dissemination of ideas.

But how could he have imagined the way information flows in to us today, when in his world telephones were primitive and rare, cinema films were silent, television and computers had yet to be conceived? Nevertheless he did, and his ideas have proved to be extraordinarily long lasting.