Notes prepared for Integrative Group B on the occasion of the 6th Network Meeting (Tokyo, August 1981) of the Goals, Processes and Indicators of Development (GPID) project of the United Nations University.

Abstract: Explores the problem of disentangling the levels of confusion which a group (or an individual) may experience when faced with a set of concepts that is beyond its collective grasp. In such a situation special dynamics are engendered around whatever parts of the set can be grasped. These take on characteristics significant for psycho social organization when different parts are comprehended by different members of the group or when the group comprehends all such parts each in turn, namely one-at-a-time only in a temporal sequence or cycle. A pattern language may be developed to take creative advantage of this tendency.

Introduction

This "paper" is a partially ordered set of notes relating aspects of:

- mathematics of human needs (cf Marcus and Mallmann (1))

- applications of combinatorial analysis of relations between finite sets, otherwise Known as Q-analysis(cf Atkin (2)3))

- pattern language (cf Alexander (4,65))

The well-established confusion amongst those subject to the complex of societal problems is now compounded by confusion and uncertainty amongst those whose roles oblige them to offer insight, guidance and solutions. At all levels of society there is a sense of impotence and despair, frequently disguised by frantic exercises in public relations, "concrete" action, and expressions of "positive" thinking. There is an increasingly deep-seated sense of insecurity and a felt inability to order and control "one's life", "to come to grips with things", "to collect one's ideas together", or to get one's act together".

Typical responses to this condition are to see it as an opportunity for asserting and imposing some particular ideology, value-system, belief-system, or mode of action. Given the current complexity of society, this can only "succeed" by forceful suppression or containment of other modes. The next decades will presumably demonstrate the ways in which such "successes" are doomed to failure.

The difficulty for an individual or group in coming to grips with this confusion lies partly in the very "language" which is used to think about and order responses to it. Over the past decades the mode of response has been largely determined through a a limited set of terms, including the following:

| problem programme project organization information | strategy research policy implementation decision | evaluation funding meeting consensus resolution | network consultation participation negotiation statement |

Such terms form a kind of "conceptual establishment" through which all activity must be channelled. Clearly there are implicit relations between the terms which govern the Kind of activity which can emerge as legitimate and appear viable.

It is perhaps time to question whether these terms, and the ways in which they ere used, do not themselves conceal a mode which is necessarily doomed to the limited effectiveness by which social action continues to be characterized. Their deadening and alienating effects on people have, for example, been noted on many occasions. It is certainly fair comment to note that the use of these terms is directly associated with the "impotence" and "sterility" of responses to the current condition.

It is useful to ask whether other languages are emerging or can be developed which would both help clarify the experienced sense of confusion and empower people and groups to act without an accompanying sense of frustration and futility. The quest is therefore for a new and more fertile mode of action which may imply a plurality of languages. The existing mode would then take on characteristics analogous to the role of scholastic Latin over the recent centuries during which it was displaced as a vehicle by living vernacular languages.

One approach to this quest is to consider the problems of comprehension associated with the confusion which was taken above as the point of departure. Clearly there is a multitude of theories, proposals and insightful initiatives being generated and advocated at this time. Their very multiplicity contributes directly to the confusion. The antagonistic and strongly competitive relationship between their advocates ultimately leaves the process of ordering them, balancing them, and using them, as the responsibility of the individual user -even if he seeks security by delegating this responsibility end accepting the consequences.

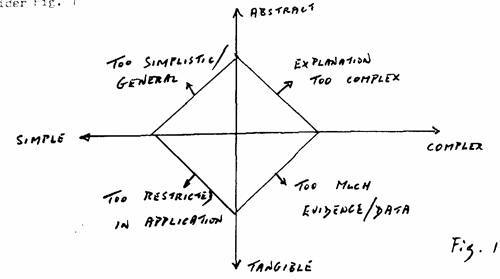

How can the individual understand his position in this whirl of social artefacts ? Consider Fig. 1

|

Each individual is effectively at the origin of such a figure. Most of the "clarifying" insights and initiatives are however perceived as lying outside the the boundary (whose existence implies that they would be perceived as much distorted, if they are perceived at all). To paraphrase, it is very much a case of "One man's insight is another man's confusion".

Combinatorial analysis of relations between finite sets (Q-analysis)

1. Q-analysis is concerned with the theory and application of mathematical relations between finite sets ( 4, 5 ). The approach is based on the use of sets at different hierarchical levels: N-1, N, N+1, etc. A set at one level may act as a cover for sets at a lower level -although, if an element of the lower level set can only be found in one element of the higher level set, the cover then constitutes a partition.

From any one level, the relations between distinct sets are the subject of 0-analysis and give rise to two views of the activities between the elements of the two sets:

global, namely an overview of the multidimensional geometric structure which can be described as the "backcloth" or "space" which supports all relevant action. Since the global geometry is not the same in all directions, it is necessary to characterize it by two associated connectivity properties:structure vector obstruction vectorThese will be considered further in a later paragraph

local, namely relatively isolated properties on different parts of the surface. Of these, the most significant are gaps in the pattern of connectivity which have been termed "holes" and are discussed further below.

2. Interpretation of 0-analysis seems to suggest that the real experience of the community by individual persons corresponds very closely to the global and local structure features to be found there. It is argued that the multidimensionality of such spaces is a matter of common intuitive experience, the limiting case of three-dimensionality being necessary but insufficient for the full range of such experiences.

Physicists make use of various patterns of connectivity in the classical 3-dimensional space to represent physical phenomena of various kinds including the dynamics of systems. "Dynamics" can therefore he regarded as synonymous with patterns", provided these patterns are associated with a suitable unchanging geometrical geometrical backcloth. In the light of the Einsteinian formulations of relativity, however, the connectivity of this backcloth can be altered by special constraints so that the geometry only permits certain positions or paths. The modified geometry then has built into it the structure characteristic of the specialized patterns invented to describe the paths in a rigid backcloth. The paths (e.g. of particles) are then not those which supposed Newtonian forces induce but rather the "natural" paths which the geometry permits.

The changes of patterns are an expression of what, in the Newtonian sense, has been traditionally called a force. In this new framework, a change in the pattern can be considered as defining a force experienced in the static backcloth in which the phenomena are to be found. And since the pattern is graded according to the level of connectivity at which it is perceived, the force will also be characterized by the level of connectivity through which it is experienced. Thus a t-force is associated with q-connectivity. There are many instances where common English usage expresses an intuitive recognition of social forces or organizational pressure experienced by people living in a structure.

3. A relation between finite sets represents a simplicial complex and this can be intuitively appreciated as a collection of abstract convex polyhedra in a suitable multidimensional euclidean space. The polyhedra are then connected to each other by sharing "faces" (namely sub-polyhedra such as edges, triangular faces, etc.). Q-analysis is the process of identifying these pieces of the simpiicial complex which are q-connected, for all values of q.

4. Distinctions of level: Q-analysis provides a more refined approach the ideologically sensitive issue of how levels are to be conceived and interrelated in psycho-social systems. It also draws attention to, and clarifies, the distinction between:

- levels as dimensionality [e.g. higher dimensionality as higher level)

- level in hierarchy (e.g. in any organizational structure)

- level of sensitivity to connectivity (e.g. ability to comprehend a complex structure, of a given level of connectivity, as a gestalt rather than by sequentially scanning its parts)

- level of psycho-social force or "pressure" resulting from changes in the pattern of connectivity over time

- level of traffic, namely the connectivity of the traffic content which can be associated with a given level but not those "below" it.

5. Traffic and noise: Q-analysis helps to clarify the distinction between "valid" communication traffic and "noise" in complex organizations or in overlapping "invisible college" networks. The interesting point is that the boundary between the two shifts according to whether the emphasis is on "efficiency" or on psycho-social development. Creating the opportunity for "noisy" traffic may in some circumstances be more important than ensuring that the traffic has a minimum noise level. It is even possible that all traffic can be usefully perceived as noise, or vice versa, depending upon the level of connectivity to which one chooses to be sensitive.

6. Evanescence of memory: Q-analysis, though its discussion of levels of sensitivity to connectivity, makes it possible to discuss with greater precision the manner in which comprehension of gestalts may be eroded over time. Such gestalts may be problems, concepts, values, organizational structures, strategies, etc.

Thus an individual or group may at some moment be sensitive to a complex pattern of high connectivity. Subsequently, however, this level of comprehension of the whole may fade in parts, reducing comprehension to that of some connected parts, or possibly to the parts in isolation only. Comprehension of the whole may be recovered periodically, and cultural events and artefacts can play a significant role in bringing this about. Or they may never be recovered, as in the case of the irreversible decline of an individual with ageing, or a group or civilization after its "golden age".

7. Multi-level communication: Q-analysis gives precision to the recognition that traffic of different degrees of content connectivity finds (or creates) its appropriate level in any psycho-social structure. Communicable insights are level hound, especially where they are of high connectivity. In other words, at the level within which we can communicate, concepts cannot be anchored unambiguously into terms and definitions which "travel well". Precision introduces distortion which is only acceptable locally within any communicating society -although "locally" most be interpreted in the non-geographical sense in which all nuclear physicists are near neighbours, for example.

This draws attention to certain implications for the development of any such structure, whether an individual, a group or a society. The most important of these would appear to be the impossibility of eliminating "undevelopment" from any such structure if it is to evolve. Such structures must necessarily continue to have traffic of very low-level connectivity co-present with that of increasingly higher-level connectivity. The simplest illustration is that of infants who will, when resources permit, continue to be educated through to the level of connectivity to which they can respond. But there will always be communication at both low and high-connectivity levels, especially about socio-political issues. The question is then how communication at these different levels of connectivity can be woven together within a social structure.

8. Co-presence of connectivity spectrum of "developments": If, as suggested above, the communication problem necessarily segments comprehension of "development", there is consequently a multiplicity of concepts of development operative in society. Individuals and groups may "progress" from one to another, possibly with a general tendency towards those of higher connectivity. But other individuals and groups will emerge and find the concepts of lower connectivity more meaningful before moving on, if they do, to those of higher connectivity. (In this sense the "ontogenesis" of an individual tends to repeat the "phylogenesis" of his/her society.) Society in this sense is the arena within which individuals and groups refine their concept of development.

But how then is the development of that society to be conceived ? Seemingly it is less a question of some "super-dominant concept" of development, and more a question of how the different developments are interrelated.

9. Holes and objects: The major achievement of Q-analysis probably lies in its ability to give precision to discussion about a psycho-social phenomenon which is, by definition, sensed beyond the boundary of (collective) comprehension. These are represented by "holes" in the pattern of connectivity. It has been argued that holes in a physical structure are indistinguishable observationally from solid objects in the physical case (3). In the psycho-social case, such holes are necessarily less substantial without losing their reality.

"Generally speaking it seems to be confirmed that action [of whatever kind) in the community can be seen as traffic in the abstract geometry and that this traffic must naturally avoid the holes (because it is impossible for any such action to exist in a hole). The holes therefore appear strangely as objects in the structure, as far as the traffic is concerned. The difference is a logical one in that the word "q-hole" describes a static feature of the geometry S(N) whilst the ward "q-object" describes the experience of that hole by traffic which moves in S(N)." ( 3, p. 75)

As an "object" this phenomenon is an obstacle to communication and comprehension and obliges those confronted with it to go "around" it in order to sense the higher dimensionality by which it is characterized. As a "hole" this phenomenon engenders, or is engendered by, a pattern of communication. It appears to function both as "source" and "sink". It is suggested that in some way which is not yet fully understood, such object/holes act as sources of energy for the possible traffic around them.

From the initial research it would appear that such objects/holes are characteristic of communication patterns in most complex organizations. It seems highly probable that they can also be detected in any partially ordered pattern of communication. As such "societal problems", "human needs", "human values" merit examination in this light.

The special value of doing so is that it can clarify why action/discussion in connection with them tends to be "circular" in the long-term, however energetic it may appear in the short-term. As such it shows how social change is blocked by the way in which conceptual traffic patterns itself around the sensed core issue which is never confronted as such because the connectivity pattern is inadequate to the dimensionality of the issue. This would explain why so many issues go unresolved and why the process of solving problems becomes institutionally of greater importance than the actual elimination of the problem.

This approach also draws attention to the probable presence of holes/objects of even higher dimensionality than those whose presence can be sensed relatively easily. Such phenomena, it may be supposed, are of great significance to long-term development.

10. Configurations of holes: Before being able to examine whether a particular concept of development is more"or less adequate, further understanding is required of how such a concept functions as a more or less stable hole/object in relation to other hole/objects corresponding to other concepts. How can such holes exist in relation to one another ? What is necessary to permit transitions from one to the other ?

The question is how configurations of holes can be identified and/or designed. It is the configuration of the holes which provides the minimum structure to stabilize and give form to the co-presence of the differing concepts of development. Such configurations, in order to fulfil their function, must presumably exist within two boundary conditions:

- the connectivity between elements bounding holes must no be so great as to erode or destroy the identity of the holes so connected

- the connectivity between elements bounding holes must be great enough so that the integrity of the configuration as a whole is maintained

A further question is then the manner whereby "better" holes are to be identified or reached within such configurations. Now from one point of view it is necessary to avoid introducing an element of evaluation, because from each hole the perception of other holes will he distorted so that no communicable assessment can be usefully formulated. On the other hand, it may prove to be the case that, at the level of the configuration as a whole, more than one such configuration can be identified/ designed in order to interrelate the perspectives associated with the set of holes. And at this level, without privileging any particular hole, more adequate inter relationships between the elements making up the holes can be identified.

Expressed differently:

- introducing evaluative judgements into the relationships between the holes within a particular configuration can only contribute to the dynamics between such holes in terms of perceived advantage/disadvantage. Excessive emphasis on this runs the risk of tearing the configuration apart. In this sense the configuration as a whole functions as a kind of "macro-hole" around which such traffic/noise circulates

- the identities associated with the holes can be respected in each of the configurations in a series constituting progressively more adequate or richer formulations of the relationships between "developments". The transitions between these successive configurations can be described with some precision such that continuity is in effect maintained. Although this "series" can usefully guide evolution of the "development set", there is a sense in which the more "primitive" configurations in the series are as valuable as those which-are: more-complex.

The characteristics of basic configuration of holes are examined in separate papers on tensegrity structures (From networking to tensegrity organization).

11. Human development: Q-analysis provides another way of discussing and interlinking certain aspects of human development. It opens the possibility of defining the individual in terms of overlapping sets of characteristics whose interrelationships can be explored with greater clarity at a new level of significance. This is of particular importance as a new language with which people can understand themselves experientially and communicate that understanding. A great advantage is that it provides pointers to those aspects of human development associated with greater connectivity ("integration") and the sensitivity stages whereby any intellectual understanding of it can be "experientialized".

The concept of holes/objects provides a very useful way of clarifying the manner in which an individual's "internal dialogue" can get locked into certain "circular patterns of reflection", or onto seemingly unresolvable issues. As discussed above, however, rather than attempting to favour the development of some of these at the expense of others, the dimension of human development which merits emphasis is that associated with "richer" configurations of these localized features.

It is the progress through the alternative perspectives provided by such configurat ions which constitutes the "changing self-image of man". The range of such configurations suggests the interesting questions: In how many distinct ways can man usefully perceive himself ? How are less useful transitions between configurat ions to be distinguished ?

As discussed above, and elsewhere (4 ), an important goal of human development would seem to be associated with the ability to shift flexibly between configurations rather than with irreversible shifts towards configurations of higher connectivity. (In traditional tales, the sage or the hero retain a special skill in communicating with children)

The structural language of Q-analysis also provides a useful means of discussing such diverse issues as: identity-and individuation [in terms of structural eccentricity), mystical or ecstatic union (as a limiting case of high sensitivity to high connectivity), rites of passage (transitions between configurations), oriental emphasis on breathing exercises (an experiential metaphor for a cycle of transitions between configurations), psychedelic drug experiences (uncontrolled shifts to alternative configurations of higher or lower sensed connectivity).

12. Social development: As in the case of human development, it is the concept of holes/objects which provides valuable insights for social development. It is probable that most continuing societal problems should be seen as holes/objects, especially given the well-established record of unfruitful action in response to them -however vigorous and dedicated. Typical examples are: peace/disarmament, development, human rights, environment, etc.

In such cases Q-analysis could provide understanding of why any action tends to be drawn into a vortex of futility, however much it satisfies short-term political needs for visible "positive" action. The participants in the action find themselves circulating" around a central concern of which they are unable to obtain an overview, due to the geometries of the overlapping conceptual and organizational structures through which they work (or which they somehow engender).

The term "futility" used above is however only appropriate if the sole consideration were the elimination of such problems. In fact the existence of such problems is extremely important to the organization of society, to social development, and to the direct or indirect employment of many people. Just as the "defence" business is vital to the economy of many countries, so is the "social problem" business vital to many sectors of society. Eliminating social problems would be a disaster for many people, especially problem-oriented intellectuals, or the employees of problem solving agencies.

As in the case of human development, it is possible that a more fruitful approach is to identify the configuration of such problem-solving bodies around the holes which engender their activity. The configuration may itself be seen as engendered by the macro-crisis hole which absorbs the development initiatives of society at this time and gives rise to the immense volume of action/communication traffic around the surface of the configuration.

Whilst it is probably neither feasible no desirable to eliminate such configurations in the name of efficiency, it is possible that the emphasis could be shifted towards alternative configurations which respect the original geometry but are more attractive because they develop it by elaboration and enrichment. A great advantage is that Q-analysis provides a measure of the obstruction to changes in the pattern of connectivity at any given level.

A major hindrance to social development is that initiatives are elaborated on the basis of the perception that some people are "right" (well-informed, objective, tolerant, etc) whereas others are "wrong" (misguided, intolerant, self-interested, etc). Effort are usually made to contain, repress or eliminate the latter. In fact as the record of every such initiative shows, those who considered themselves "right" had significant blindspots, and the arguments of those who were "wrong" were not without validity. It is even possible that lasting social development only results from the interaction of such initiating and constraining tendencies, but only when some"creative compromise is achieved to correct for the self-righteousness and bigotry of each tendency.

Through its use of "anti-vertices" Q-analysis offers a powerful tool for handling such essential differences with greater clarity. This appears important, not only in the light of the preceding paragraph, but because of the way in which social development is fuelled by difference. The drive to social development is fuelled, paradoxically, by the differences which that development (as presently conceived) strives to eliminate. Once eliminated the society would be in danger of stagnation or of instabilities in reaction to that stagnation. For this reason a more creative attitude is required to those ever-present conditions which engender difference, namely: ignorance, apathy, intolerance, etc. They can usefully be considered as "fuel elements". But energy can only be usefully generated from them if they are bound into a suitable configuration with those elements which react to them. The question is how to detect or design configurations which can channel and focus social energy in this way.

The above argument implies the existence of one kind of social "energy" which is vital to the life and development of society. Analysis of configurations may well bring to light other kinds of social energies which have to be kept in balance. Oriental traditions highlight the existence of many distinct sets of energies "nested" in relation to one another ( ). But the difficulty is to sense the complementarity between them. Without this understanding, the manner in which they function as a "team" is unrecognized and those identifying with particular energies are trapped in the dynamics of the configuration in question.

Pattern language: a timeless way of building

1. Q-analysis provides us with a remarkable tool for analysis. It has not yet been developed to the point where we can use it for building new social structures. It lacks, perhaps necessarily, the essential art of design or synthesis. For this reason it is useful to consider another remarkable development of recent years, namely the elaboration of a pattern language (6, 7, 8 ). Ironically, both Q-analysis and this pattern language have been applied to the design-type problems of two complex universities, Essex and Oregon (3,9). The complementarity of the two approaches remains to be recognized.

2. The main contribution of the pattern language is perhaps an understanding of how constraints can be creatively handled to enhance the quality of life as experienced by those functioning in a complex institutional setting. It focuses on the democratization of the design process. To date the concern has been primarily with the impact on the physical design (buildings, towns, regions), but many social and organizational questions are necessarily considered in a new way.

3. Despite its practicality, the essential charm from a development perspective is its emphasis on maximizing expression of what is termed the "quality without a name" - it being nameless because of the recognized limitations of each label so freely bandied about in social policy making. And it is precisely in the caution with which patterns are developed to "contain" this subtle, many facetted, quality that much of value could be derived for human and social development in a wider sense.

4. The major achievement lies in the detection and extensive description of 253 patterns which can be combined in different ways by the user (group) to form the unique language significant to that user. It requires little imagination to see the challenge of elaborating a similar set of psycho-social patterns with which a user (group) could elaborate a language to design alternative institutions and lifestyles.

5. A significant feature of the presentation of the pattern language is its success as a form of presentation -despite its practicality and its foundation on well-argued theoretical grounds. It is no exaggeration to note that the "nameless quality" which the initiative aims to maximize is present in the presentation itself, as the following chapter abstracts may illustrate: (see Insert 1).

Annex I: The Timeless Way(Reproduced from Christopher Alexander The Timeless Way of Building. New York, Oxford University Press, 1979 (vol. I) |

A building or a town will only be alive to the ex tent that it is governed by the timeless way. 1. It is a process which brings order out of nothing tut ourselves; it cannot be attained, but it will happen of its own accord, if "we "will only let it. THE QUALITY To seek the timeless way we must first know the quality without a name. 2. There is a central quality which is the root criterion of life and spirit in a man, a town, a building, or a wilderness. This quality is objective and precise, but it cannot be named, 3. The search, which we make for this quality, in our own lives, is the central search of any person, and the crux of any individual person's story. It is the search for those moments and situations when we are most alive. 4. In order to define this quality in buildings and in towns, we must begin by understanding that every place is given its character by certain patterns of events that keep on happening there. 5. These patterns of events are always interlocked with certain geometric patterns in the space. Indeed, as we shall see, each building and each town is ulti mately made out of these patterns in the space, and out of nothing else: they are the atoms and the mole cules from which a building or a town is made. 6. The specific patterns out of which a building or a town is made may be alive or dead. To the extent they are alive, they let our inner forces loose, and set us free; but when they are dead, they keep us locked in inner conflict. 7. The more living patterns there are in a place- a room, a building, or a town-the more it comes to life as an entirety, the more it glows, the more it has that self-maintaining fire which is the quality without a name. 8. And when a building has this fire, then it becomes a part of nature. Like ocean waves, or blades of grass, its parts are governed by the endless play of repetition and variety created in the presence of the fact that all things pass. This is the quality itself. THE GATE To reach the quality without a name we must then build a living pattern language as a gate. 9. This quality in buildings and in towns cannot be made, but only generated, indirectly, by the ordinary actions of the people, just as a flower cannot be made, but only generated from the seed. 10. The people can shape buildings for themselves, and have done it for centuries, by using languages which I call pattern languages. A pattern language gives each person who uses it the power to create an infinite variety of new and unique buildings, just as his ordinary language gives him the power to create an infinite variety of sentences. 11. These pattern languages are not confined to vil lages and farm society. All acts of building are gov erned by a pattern language of some sort, and the patterns in the world are there, entirely because they are created by the pattern languages which people use, 12. And, beyond that, it is not just the shape of towns and buildings which comes from pattern lan guages-// is their quality as well. Even the life and beauty of the most awe-inspiring great religious build ings came from the languages their builders used. 13. But in our time the languages have broken down. Since they are no longer shared, the processes which keep them deep have broken down; and it is therefore virtually impossible for anybody, in our time, to make a building live. 14. To work our way towards a shared and living lan guage once again, we must first learn how to discover patterns which are deep, and capable of generating life. 15. We may then gradually improve these patterns which we share, by testing them against experience: we can determine, very simply, whether these pat terns make our surroundings live, or not, by recog nizing how they make us feel. 16. Once wee have understood how to discover indi vidual patterns which are alive, wee may then make a language for ourselves for any building task we face. The structure of the language is created by the net work of connections among individual patterns: and the language lives, or not, as a totality, to the degree these patterns form a whole. 17. Then finally, from separate languages for differ ent building tasks, we can create a larger structure still, a structure of structures, evolving constantly, which is the common language for a town. This is the gate. THE WAY Once we have built the gate, we can pass through it to the practice of the timeless way. 18. Now we shall begin to see in detail how the rich and complex order of a town can grow from thousands of creative acts. For once we have a common pattern language in our town, we shall all have the power to make our streets and buddings live, through our most ordinary acts. The language, like a seed, is the genetic system which gives our millions of small acts the power to form a whole. 10. Within this process, every individual act of build ing is a process in which space gets differentiated. It is not a process of addition, in which preformed -parts are combined to create a whole, but a -process of un folding, like the evolution of an embryo, in which the whole precedes the parts, and actually gives birth to them, by splitting. 20. The process of unfolding goes step by step, one pattern at a time. Each step brings just one pattern to life; and the intensity of the result depends on the in tensity of each one of these individual steps. 21. From a sequence of these individual patterns, whole buildings with the character of nature will form themselves within your thoughts, as easily as sentences. 22. In the same way, groups of people can conceive their larger public buildings, on the ground, by fol lowing a common pattern language, almost as if they had a single mind. 23. Once the buildings are conceived like this, they can be built, directly, from a few simple marks made in the ground-again within a common language, but directly, and without the use of drawings. 24. Next, several acts of building, each one done to repair and magnify the product of the previous acts, will slowly generate a larger and more complex whole than any single act can generate. 25. Finally, within the framework of a common lan guage, millions of individual acts of building will together generate a town which is alive, and whole, and unpredictable, without control. This is the slow emergence of the quality without a name, as if from nothing. 26. And as the whole emerges, we shall see it take that ageless character which gives the timeless way its name. This character is a specific, morphological char acter, sharp and precise, which must come into being any time a building or a town becomes alive: it is the physical embodiment, in buildings, of the quality with out and name. THE KERNEL OF THE WAY And yet the timeless way is not complete, and will not fully generate the quality without a name, until we leave the gate behind. 27. Indeed this ageless character has nothing, in the end, to do with languages. The language, and the processes which stem from it, merely release the fun damental order which is native to us. They do not teach us, they only remind us of what we know al ready, and of what we shall discover time and time again, when we give up our ideas and opinions, and do exactly what emerges from ourselves. |

References

1. Carlos Mallmann and Solomon Marcus. Empirical information and theoretical constructs in the study of needs.

2. C. Calude, Solomon Marcus, et al. Mathematical paths in the study of human needs. Tokyo, United Nations University, 1981, HSDRGPID-46/UNUP-160

3. Ron Atkin. Combinatorial Connectivities in Social Systems; an application of simplicial complex structures to the study of large organizations. Basel, Birkhauser, 1977

4. Ron Atkin. Multidimensional nan; can man live in 3-dimensional space ? London, Penguin, 1981

5. Ron Atkin. Mathematical Structures in Human Affairs. London, Heinemann, 1974

6. Christopher Alexander. Notes on the Synthesis of Form. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1964

7. Christopher Alexander. The Timeless Way of Building. Oxford University Press, 1979 (vol. I)

8. Christopher Alexander. A Pattern Language: towns, buildings, construction. New York, Oxford University Press, 1977 (vol. II)

9. Christopher Alexander, et al. The Oregon Experiment. Oxford University Press, 1975 (vol. III)

10. Anthony Judge. Integrative dimensions of concept sets; transformations with minimal distortion between implicitness and explicitness of set representation according to constraints on communicability. (Paper prepared for Group B of the United Nations University GPID Project, Tokyo. August 1981